A week after the attack on Fort Sumter in April, 1861, Dorothea Dix made her way to Baltimore, Maryland to offer her services to aid wounded soldiers. Finding inadequate, improvised hospitals, she volunteered to aid the War Department. Despite her lack of experience, Dix was named Superintendent of Army Nurses, requiring her to obtain medical supplies and hire and train women nurses. Known for her stern and inflexible demeanor, she implemented strict guidelines for women to volunteer as Army nurses, selecting “plain looking” between the ages of 35 and 50 with an authorized dress code of modest black or brown skirts and forbade hoops or jewelry. Dix pushed for formal training for the female nurses under her command and eventually convinced some skeptical military officials that women were up to the task. She appointed over 3,000 women as Army nurses during the course of the war.

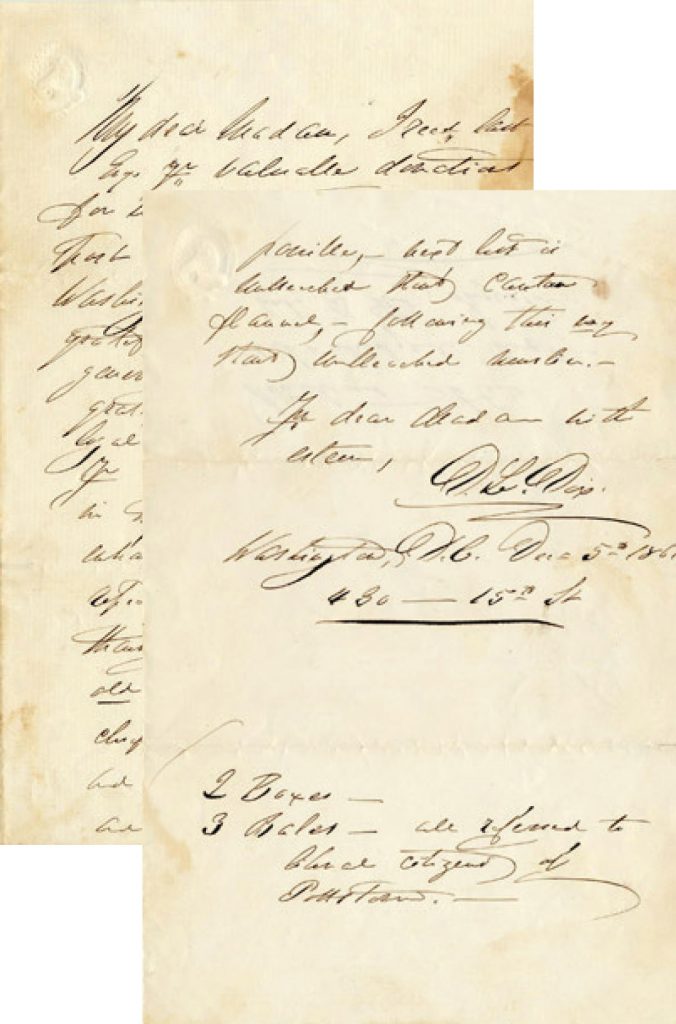

Serving as Superintendent without pay through the entire war, Dix worked untiringly to aid the patients under her care, often times at the detriment of nurses who came to fear her, leading to nicknames the “Dragon Dix” and “Dictator in a Petticoat”. Dix clashed frequently with the military bureaucracy and occasionally ignored administrative details. She often obtained medical supplies, linens, fruit, and bedclothes from private sources when they were not forthcoming from the government and irritated some radical republicans by insisting that captured rebel soldiers be given identical care. Army nursing care was markedly improved thanks to her leadership. She never took a day off in the entire four years of the war. In this December 5, 1861 manuscript, Dix thanks L.A. Richards of Pottstown, Pennsylvania for a donation and then asks for more material:

I should be thankful for a large stock of old and new pocket handkerchiefs—common sorts: shirts and drawers of common sizes and patterns: flannel if possible—kept best in unbleached state certain flannel—following this say standard unbleached muslin.

After the war, Dix continued her work in the reforms of jailhouses and asylums until she was in her eighties. Her death in 1887 was lamented by hundreds of soldiers, both North and South, whose lives she had helped save.