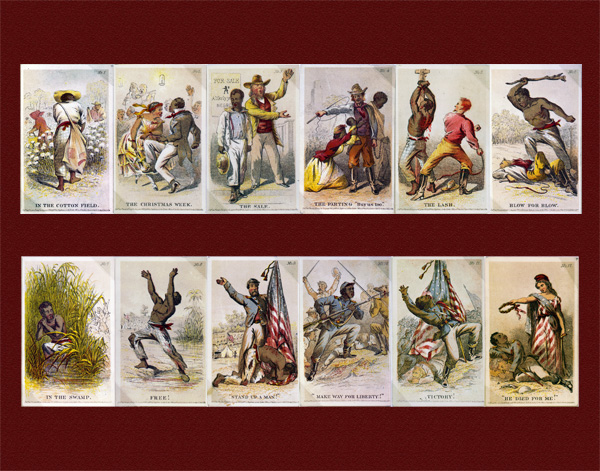

Great Britain introduced the institution of slavery in the American Colonies in the seventeenth century. At the time of the revolution, all thirteen colonies permitted slavery, but by 1804 each of the northern states had provided for its abolition. States in the South fiercely defended slavery as a foundation of their economies. In the Constitution, the three-fifths compromise acknowledged slavery by counting each free person and “three fifths of all other Persons” for the purpose of enumeration, when calculating the number of representatives to Congress from each state. It also provided the “Fugitive Slave Clause”, and that the importation of people could be ended, but not until 1808.

Lincoln’s election as President in 1860 signaled a significant shift, precipitating articles of secession passed by southern states, first with South Carolina and others following, in an attempt to preserve the institution of slavery. When Lincoln took office in 1861, some four million people were enslaved in the United States.

When reading the declarations of secession by the states in rebellion, it is clear that slavery was the central issue. It would take four years and hundreds of thousands of lives to preserve the country and finally end the horrific scourge of slavery.